If it looks like a Rock Opera, smells like a Rock Opera, then……

I was tempted, in true 1970s style, to offer an enigmatic explanation that offered more questions than answers, but as Lost In The Ghost Light has nothing to do with cosmic coincidences or creatures of myth and legend (well, perhaps something of the latter), I felt a straightforward breakdown of the inspiration would do.

It all started with me seeing a sixty something jogger in an expensive tracksuit rifling through the vegetable racks at my local Co-Op. His intense glare combined with his thinning long grey hair and Mick Fleetwood beard left me wondering which veteran Rock band he’d once played with.

This got me thinking about the moment when music first came into this person’s life and whether it still informed his music making in the present. Other questions followed about the tensions between commerce and art, career and idealism: Could the creative ‘spark’ be lost then re-discovered?; What were the costs of dedicating a life to music and how much did ‘real’ life get in the way of the ‘magic’?; What was the effect of the changing nature of the industry on music itself as physical objets d’art became unpaid streams?; Were, as Brian Eno suggested, professional musicians like blacksmiths, echoes from another age and, if so, what was the impact of that realisation on a performer playing to an ageing crowd?

I’m fascinated by the iron grip that music has on the lives of musicians and fans alike. What’s still portrayed as a teenage obsession can have an unshakeable hold on people until the end of their lives.

Personally speaking, I feel as passionately about both my own music and other people’s as I ever did. There have been heady highs and dismal lows since I signed my first deals in the early 1990s, but the emotional and transformative qualities of listening to or creating a song (or an album) remain constants in a life of changes.

On my own and alongside musical collaborator Stephen Bennett, I started working on what became Lost In The Ghost Light in 2009. Feeling I’d never finish it to my satisfaction, songs intended for the album appeared on Abandoned Dancehall Dreams (Dancing For You and The Songs Of Distant Summers), Stupid Things That Mean The World (the title track and The Great Electric Teenage Dream), or remained in limbo. Pretty much out of nowhere, You’ll Be The Silence, You Wanted To Be Seen and Lost In The Ghost Light were written in a flurry of activity in Spring 2016. The project was back on! Distant Summers followed soon after, in June, and provided the logical ‘Rosebud’ conclusion I’d been looking for.

In spite of its long gestation period, the album felt (and feels) like one of the most cohesive I’ve been involved in making.

————

Stupid Things That Mean The World represented a continuation and extension of the moods and ideas on Abandoned Dancehall Dreams. Partly as a response to the nature of ‘the concept’, Lost In The Ghost Light is a departure from both.

Amongst other influences, Abandoned Dancehall Dreams and Stupid Things That Mean The World drew on the early 1980s Art Rock/Art Pop I listened to when I started singing in bands (Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel, Brian Eno, Talking Heads, Laurie Anderson, XTC, Thomas Dolby, Japan and so on). For me, this was an innovative but relatively neglected area of music that still seemed to offer contemporary potential in the 2000s. I was always surprised that the wonderful fusions of Pop, experimentation, Classical Minimalism, pummelling drums and fearless ambition on albums such as The Hounds Of Love, Mr Heartbreak, Mummer and Peter Gabriel 4 didn’t create a movement in their wake. For me, these were albums that suggested musical futures rather than the brilliant creative dead ends they largely ended up as being.

By contrast, Lost In The Ghost Light draws from an equally complex set of source influences, but ones that have frequently been referenced or regurgitated.

Step up the love that dare not speak its name.

When I first got into music in the mid to late 1970s, Progressive Rock was a huge influence. I was a big fan of many things (10cc, Beatles, Bowie, John Barry, Patti Smith, The Stranglers, Donna Summer/Giorgio Moroder and more), but at the time – bar my love for the work of Kate Bush – ‘Prog’ (top) trumped them all. Contrary to its reputation for being distant, bloated and exhibitionist, for me it provided an emotional release from a difficult adolescence. The fact that most people I knew hated it, possibly made it even more of a personal passion!

Whether it was the sentimental beauty of a Genesis ballad, the atmospheric explorations of Pink Floyd, the nostalgic eccentricity of the Canterbury scene, the giddy inventiveness of Gentle Giant, or the brute-force of VDGG and King Crimson, I was transported by a world of creative possibilities to somewhere more interesting than suburban Warrington. I was excited and moved by albums like Pawn Hearts, Close To The Edge, Rock Bottom, Incantations, Foxtrot, Free Hand, The Civil Surface, Lifemask, In The Land Of Grey And Pink, Islands, Dark Side Of The Moon and many more.

As much as my tastes have evolved over the years and my own music developed along different paths, the idealism of Progressive music remains a touchstone. Prog may have been occasionally ridiculous, pompous, and overreaching, but it was rarely boring. On a personal level, it also acted as a gateway to Classical, Folk, Jazz, Psychedelic and other types of music that had been influential on Progressive itself.

As with my interest in 1980s gated tribal drums and Prophet 5 textures, it’s probably an accident of birth that the 1975-1979 Symphonic Rock sound palette of Novatrons, Solina Strings, Oberheim Polyphonics, Taurus Pedals, ARP Pro Soloists, and Yahama CP 70s is profoundly evocative to me along with many of the albums it prominently featured on (And Then There Were Three, Wish You Were Here, Moonmadness, Danger Money, Heavy Weather, Spectral Mornings etc). As part of Ghost Light dwells on the way the Punk revolution destabilised a certain type of ‘classic’ Rock music/musician, I was keen to exploit and explore these sounds anew as they struck me as representing something of a grand romantic gesture in the face of the harsh contemporary musical and political environment of the late 1970s.

————

2016 has been a bruising year in terms of societal divisions being exposed in the West, ongoing wars in the Middle East, and the deaths of prominent cultural figures. Part of me wonders whether the musical elements of Lost In The Ghost Light are something of an unconscious ‘retreat into beauty’; an emotional release from a difficult time; an attempt to find comfort and certainty by reaching out to a fondly remembered aspect of the past. That said, escapism can be a valid, sometimes necessary creative response to a brutal present, and maybe, in its own (special) way, Ghost Light is as much a reflection of how some of us feel now as The Life Of Pablo or Blond?

————

In 2012, I played two of the Ghost Light demos (what became Moonshot Manchild and Worlds Of Yesterday) to Steven Wilson as possible no-man songs. At the time he was assembling ideas for The Raven That Refused To Sing and he immediately connected with the material while feeling it was wrong for no-man.

As on many an occasion, we’d arrived in a similar place at a similar time entirely coincidentally.

In some respects, Ghost Light is my equivalent to The Raven, in that on that album Steven took the aspects of 1960s/1970s Progressive music that spoke to him and turned them into an expansive and emotional statement that referenced the past without becoming a slave to it and without sacrificing his own identity. In a different way, that’s what I was attempting to achieve with Lost In The Ghost Light.

A single bulb on a stand in the centre of a stage, a ghost light is the only source of illumination in a deserted theatre at night.

As on Abandoned Dancehall Dreams, having very fixed images – backstage and onstage reflections in this case – proved liberating as well as unifying. Once the album’s themes and atmospheres were established, the lyrics ran free. Whereas I’d written a lot of the music on Abandoned Dancehall Dreams and Stupid Things That Mean The World, this time I concentrated on lyrics, vocal melody, structure, album sequencing and arrangements, while Stephen Bennett provided much of the musical spine (along with a more sophisticated chordal language than I’m capable of).

More so than on any previous project, the lyrics and vocal performances were subject to frequent revisions. As on Stupid Things That Mean The World, I recorded the vocals in my home studio, but this time I was far stricter in terms of what I’d accept. While Distant Summers was comprised of an edit of two takes, the likes of Moonshot Manchild and You’ll Be The Silence were the result of 50 plus vocal takes and many hours of editing and cleaning up. Despite Ghost Light effectively being a story about something and someone removed from my own experiences, the making the album and the performance of the songs were no less emotionally engaging or intense than my more obviously ‘personal’ projects.

Through the creation of a band and singer from the so-called ‘Golden Age of Rock’ (Moonshot and Jeff Harrison, now you’re asking), I was attempting to capture the ‘everything and nothing’ grand folly that music obsession can represent. I wanted to explore both the majestic and mundane elements of ‘the Rock life’, while also addressing the seeming permanence of transient fads and the fact that most of us are imprisoned in specific pockets of cultural (as well as actual) time. The album revolves around the contemporary musings of Jeff Harrison, but the events in the songs take place between 1967 and 2017.

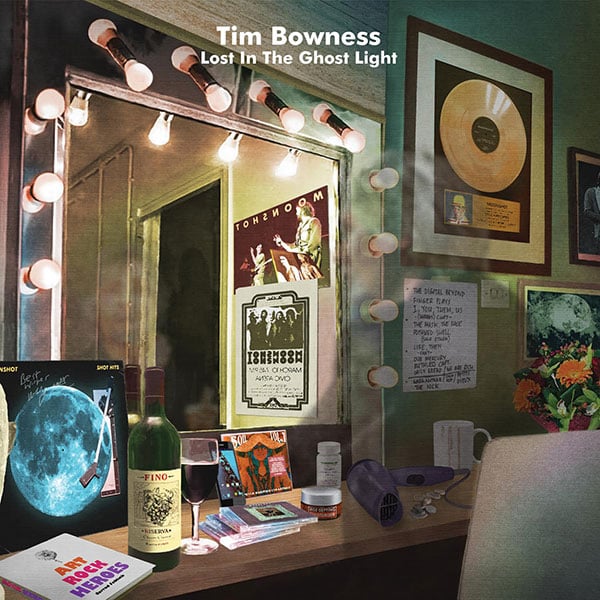

I put together a creative and career timeline for Moonshot that Jarrod Gosling beautifully realised in his artwork. For me, it’s the strongest of Jarrod’s covers and his superb evocation of period detail alongside the album covers spanning the decades of Moonshot’s releases is exactly what I’d imagined and more.

————

Getting Ian Anderson to play on Distant Summers was an unexpected thrill. His playing on the song is astonishing, sensitive and emotional and provides exactly the lift the piece needs at exactly the time it needs it. As someone who has admired Ian’s work ever since buying copies of Aqualung, Heavy Horses and Stormwatch in 1979, it was a genuinely moving experience to hear his typically unique contribution to one of my pieces.

Equally thrilling was the involvement of Kit Watkins. Kit was the keyboard player at one of the first gigs I attended (Camel at the Manchester Apollo in 1981) and like Ian provided some great playing as well as an authentic link to a few of the musical inspirations behind the album.

Elsewhere, Colin Edwin played a wonderfully diverse set of parts (from fretless to acoustic to distorted electric bass), Andrew Booker was at his most rhythmically and sonically adventurous, Stephen Bennett was at his most symphonic and lush, Hux Nettermalm was wholly appropriate with his effortlessly relaxed grooves, Bruce Soord stepped up to the ‘Guitar Hero’ role like a natural, Steve Bingham brought class and quality to whatever he played on, and Andrew Keeling was once more responsible for some extraordinary string arrangements in addition to some lovely flute contributions.

Add Steven Wilson’s ever evolving mixing and mastering skills to the above and the end result is something I’m genuinely proud of and attached to.

————

Stupid Thing That Means The World:

Lost In The Ghost Light is an album about the reflections of a particular type of half-remembered musician in the present day, but it’s also a love letter to the memory and ongoing influence of a teenage passion that lingers.

Tim Bowness, 17th December 2016

————

Find out more about Lost In The Ghost Light on Tim’s website